Understanding your industry with the Five Forces

the classic framework from Michael Porter

Porter’s Five Forces

Permalink to “Porter’s Five Forces”To kick things off for the new year, I’m going to zoom out to the big picture, and look at a model that looks at entire industries.

While this might seem abstract and remote from building products and services, your daily activities take place in the context of a web of relationships and interactions between producers, customers, suppliers and the wider economy.

Understanding the environment that you’re operating in is crucial to effectively planning and running a business. You can have the most technologically-sophisticated product imaginable, but if you don’t understand the dynamics of how your customer and competitors operate, you’ll struggle to survive in the long run.

It’s also relevant to the day-to-day grind, too. If you occasionally take a glance at the bigger picture, it can help give you context that helps when it comes to making decisions about which technologies to exploit, or how to prioritise competing requests for feature development.

Why strategy matters

Permalink to “Why strategy matters”Setting your strategy - what your aim(s) are and how you’re going to go about reaching them - affects every aspect of the business. That’s one of the reasons why it’s an incredibly well-researched area - a quick search for books with some variation of “business strategy” returns pages and pages of results.

There are countless frameworks for analyzing markets, ranging from trivial to incredibly sophisticated. To me, though, there’s a bit of law of diminishing returns in action - the more complicated your analysis, the more assumptions about the raw data going into that analysis, and the greater the risk that your conclusions are based on false presumptions.

A model which strikes the balance between simplicity and sophistication, then, is the famous Five Forces Framework. Developed by the Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter, it first appeared as an article in Harvard Business Review in 1979, and later expanded into a full-length book.

Although the model is quite approachable, the book (in my opinion at least) isn’t so much - it's over 500 pages thick, the prose is bone-dry, and it’s a bit of a slog. The good news is that I’ve read it, so you don’t have to…

What’s the framework for?

Permalink to “What’s the framework for?”The Five Forces Framework is a structure for understanding and analysing the environment that a business is operating in, in order to understand how intense the competition is; where the competition comes from; and help make decisions about how to respond.

Crucially, it considers not only your obvious competitors: the rival products and services that your customers could choose instead of yours; but also the competitive forces that aren’t part of products and services already in the market: customers, suppliers and potential new entrants.

Two concepts underpin the whole model: firstly, that the greater the competition in an market, the harder it will be to make a profit - or more specifically, a profit that’s attractive enough to either enter, or stay in the market.

The definition of how much profit is sufficient obviously varies from industry to industry, and company to company - but the underlying assumption is that you’ll want to make at least some profit over a reasonable period in order to operate in the market in the first place.

The second idea assumes that in a perfect market, the interaction of the competitive forces will eventually drive profits down to a “floor” level, where every player in the market makes the same amount.

To break out of this pattern, you need to innovate in some way - for example, if you can produce your product more efficiently, you’ll be able to lower your costs and therefore increase your profits. Another approach would be to make your product more attractive by adding improved features.

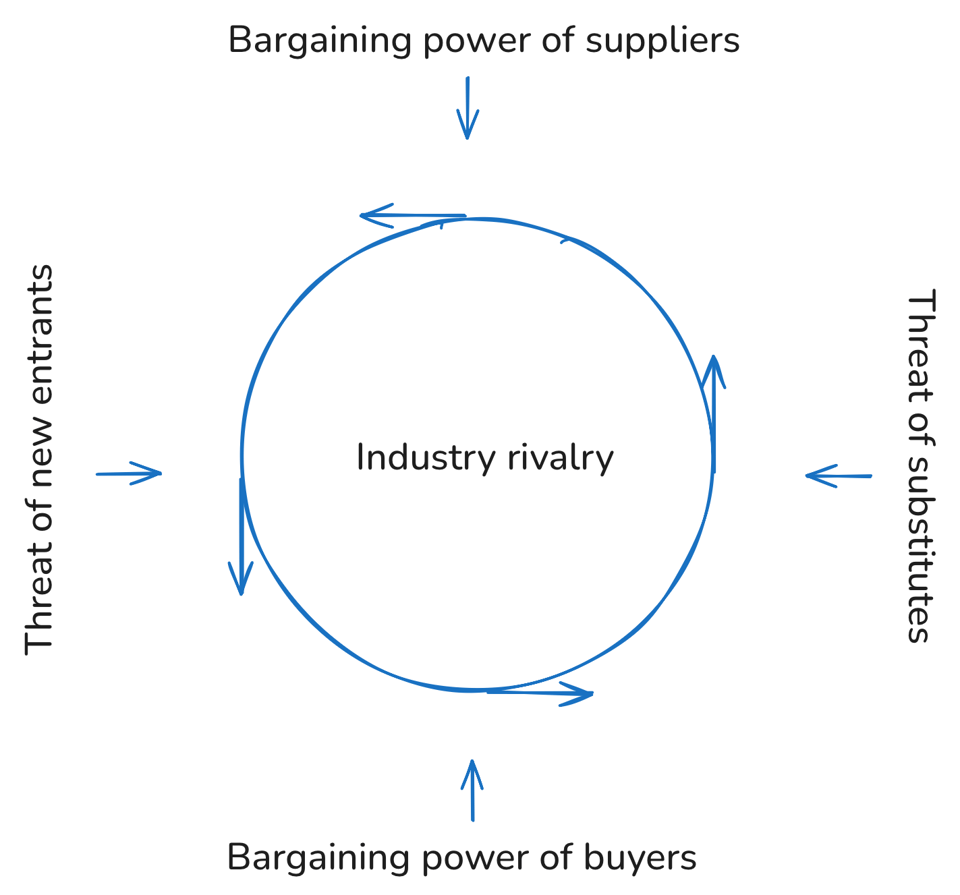

Against the background of those two ideas, the framework looks at the the level of competition in a market as the result of five forces - the threat of new entrants; the bargaining power of your customers; the bargaining power of your suppliers; the threat of alternatives substitutes for your product or service; and the level of competition or rivalry between the you and your competitors.

The five forces framework gives you a structured way of cutting through some of the messy complications of real life, and look systematically at what’s going on around you.

The elements of the framework

Permalink to “The elements of the framework”

At the centre of the model are the firms that operate in the industry itself. They operate in a state of constant industry rivalry, competing on price and product to win customers. From outside the industry comes the threat of new entrants, who seek to get a foothold and win customers from the incumbents. There is also the threat of substitutes, rival products and services that could replace yours. In the production and development process the bargaining power of suppliers affects the cost of your product and therefore the marginal profit, while the bargaining power of buyers constrains the price that you’d like to be able to charge.

The threat of new entrants

Permalink to “The threat of new entrants”How likely is it that more competitors will start offering the same product or service that you do?

Launching a new product or service isn’t free - you’ve got to build it, launch it, market it to attract customer attention, then win customers away from the existing rivals. Depending on the nature of the product, those can range from “trivially easy” to “impossibly hard”. The easier these are, goes the thinking, the more likely it is that rivals will try to do what you’re doing, and steal market share away from you.

Barriers to entry into a market can take all kinds of forms, both obvious and hidden. If you wanted to start a new airline, for example, you’ll need seriously deep pockets. Leasing aircraft and setting up all the necessary infrastructure - ticket sales, handling agents, flight crews etc etc is both necessary, complicated and expensive.

And that assumes that you’re allowed to try in the first place - regulatory barriers might prevent you from operating in the first place. To fly in the US, you’ll need the approval of the Federal Aviation Authority. They exist to enforce standards to stop planes falling out of the sky, which means you won’t be allowed to cut corners even if you need to in order to run your new service at a profit.

Viewed from one perspective, the software industry has low barriers to entry because there’s very little need for big, expensive infrastructure like factories and production lines. Starting a new company to build a rival to SAP could be (in theory) be done very quickly - you wouldn’t even need offices, if you opted to build remote teams. On other hand, there will be significant challenges in finding software developers with expertise to build this, and then you’ll have the challenge of persuading customers to switch to your product.

Another factor which affects how likely you are to be subject to new competition in the future is how existing players will react to new ones. If you’re well-established, with good revenues and plenty of retained profits, you can probably afford to drop your prices to compete with or even undercut new entrants for long enough that they’re driven back out.

Threat of substitutes

Permalink to “Threat of substitutes”How easy is it for your customers to switch to your rivals?

This is affected by numerous factors - the cost to customers of switching to an alternative; how feasible it is for them to find an alternative to your product; how many other similar products are out there; and how likely customers are to think of switching in the first place.

An example of an industry where customer switching costs are very low is supermarket retailing. Minor details like branding and location aside, one supermarket is very like another - in fact, they probably sell exactly the same products for more or less the same price. As a food shopper, you can very easily buy from another store - which makes the threat of substitutes in the industry a very real one.

At the other extreme, there might only be one game in town. If you want to set up a semiconductor fabrication plant, AMSL is the only company in the world that makes deep ultraviolet lithography machines. Even if you balked at their prices, you have no alternatives. While this lack of substitutes might suggest the market is ripe for disruption, the billions in startup costs and decades of development needed mean ASML faces very little threat of substitution.

Another very important factor that affects the threat of substitutes the disruption involved in customers switching from you to a rival. If it’s easy for customers to move to a new entrant into a market, that makes the market as a whole look more attractive. There’s a greater chance that new entrants will be to win customers away from you and the existing players.

A practical example of this is number portability in the mobile telecoms market. Until relatively recently, if you wanted to switch mobile phone providers you also needed to change your phone number - very disruptive. That’s changed as a result of regulators forcing the telecos to make it possible - so now it’s relatively painless. As an upstart mobile operator, that makes the job of winning new customers much easier.

Bargaining power of customers

Permalink to “Bargaining power of customers”How much power do your customers have?

There’s a saying in the financial world that if you owe the bank a million dollars, you’ve got a problem. But if you owe the bank 10 billion dollars, then it’s the bank that has the problem.

Customer bargaining power significantly affects market attractiveness. When customers have multiple alternatives or other leverage, you'll find it harder to adjust prices or conditions to improve profits

The bargaining power of customers is inextricably linked with the other forces - how substitutable your product is, how likely it is that there will be alternative suppliers delivering it, and so on. If you’re a monopoly supplier, customers are less powerful - but true monopolies are very rare, and the more advantage you take of your customer’s captivity, the greater the risk that they’ll become more flexible in what they consider to be an acceptable substitute.

Bargaining power of suppliers

Permalink to “Bargaining power of suppliers”How easy is it for my suppliers to call the shots?

In order to make your product or service, you need inputs - whether that’s financial, physical or intellectual. Markets where the supplier call the shots can be difficult to work in, and that can in turn affect how much returns you’ll be able to make.

This can be a function of how commoditised your supplies are. To think about the chip manufacturing business again - there are only a handful of companies in the world who have the expertise to build the machinery you’ll need, and the equipment is incredibly complex. It would be very difficult to switch to another supplier if you were unhappy with your incumbent raising their prices, so they have a lot of power over you.

If on the other hand your main inputs are easily obtainable commodities - oil products for example - then the roles are reversed and you’ll have suppliers coming to you. In this scenario you can switch easily, so a supplier that tries to raise prices or change terms too far will find out the hard way that they’re relatively powerless.

Software doesn’t really need raw materials as such, but you do need software engineers to build it. Right now, skills and experience in AI are in great demand, so anyone with that expertise is able to pick and choose their employer. “Generic” front-end or backend skills? Maybe not so much.

Competitive rivalry

Permalink to “Competitive rivalry”How dynamic is the competition between firms that are already in the market?

Some markets are ruthlessly competitive - just look at the endless mobile phone discounts and offers. Today's innovative product becomes tomorrow's outdated offering, forcing constant investment in product management and marketing just to maintain position.

At the other extreme, the market might have been carved up between a couple of big incumbents who are snoozing quietly because nothing much ever changes. In that situation, it could potentially be a lot easier to land with a splash and shake things up as a new entrant - or even an incumbent who juices up their own product line.

Technical innovations have a part to play here, too - if your competitors are constantly improving the formulation of their products, you’ll have to invest in product development to keep up. This is definitely the case in the software industry - customers are used to a constant flow of new features, so if you’re tempted to save costs by downsizing your engineering teams, that will come back to haunt you very quickly.

Pricing rivalry can be a significant factor in the attractiveness of an industry - even if you’ve got good margins to begin with, if you have to discount them away to keep up with rivals that can seriously constrain your survival chances.

SaaS products are a fascinating example of how competitive rivalry works - there are clear cycles where new and innovative companies pop up, fight it out to the death, and the winners then grow old and stale and complacent. Until dissatisfaction grows, new innovators appear, and the cycle starts all over again…

Putting it all together

Permalink to “Putting it all together”Although each of the five forces can be considered independently, there’s obvious interrelationships which have to be taken into account.

Barriers to entry from customer switching costs, for example, are also related to how much bargaining power customers have. The idea is to build up a balanced picture to get an overall impression of the dynamics of the industry - and then use that to help determine the right strategic response.

The main takeaway from the framework is that it’s important to look beyond the obvious sources of competition that you face, and consider where you might be able to find an advantage that’s harder for rivals to match or beat.

Further reading

Permalink to “Further reading”How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy The original 1979 HBR article that set all this off (this link is paywalled, but a quick Google search will throw up numerous accessible versions)

Competitive Advantage The 1985 book, which expands in much greater depth on the framework. This is one mainly for the aficionados, but it looks good on your bookshelf even if you don’t read it

The Five Competitive Forces That Shape Strategy - a YouTube interview with Michael Porter where the framework is explained by the man himself